As one of the most pressing global challenges, climate science relies on clear, accurate, and credible communication of research findings, often in the form of formal scientific articles.

So, what happens when the integrity of those papers’ abstracts is called into question?

The emergence of large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT has made it increasingly easy for researchers to draft scientific content, including abstracts, with minimal effort. However, generative AI tools aren’t perfect and have been known to hallucinate and make mistakes.

Without proper oversight, it’s therefore possible that AI-generated climate change abstracts may not be as accurate as they should — or need — to be.

Since it’s often the first (and in some cases, only) portion of a paper read by policymakers, media, and the general public, maintaining the integrity of abstracts is crucial not only academically, but also socially and politically.

Due to this influence, this study examines the prevalence of AI-generated abstracts in climate change-related publications from 2018 to 2025 and assesses implications for the growing role of AI in scientific authorship.

Based on thousands of climate change abstracts collected from 2018 to 2025, this study aimed to:

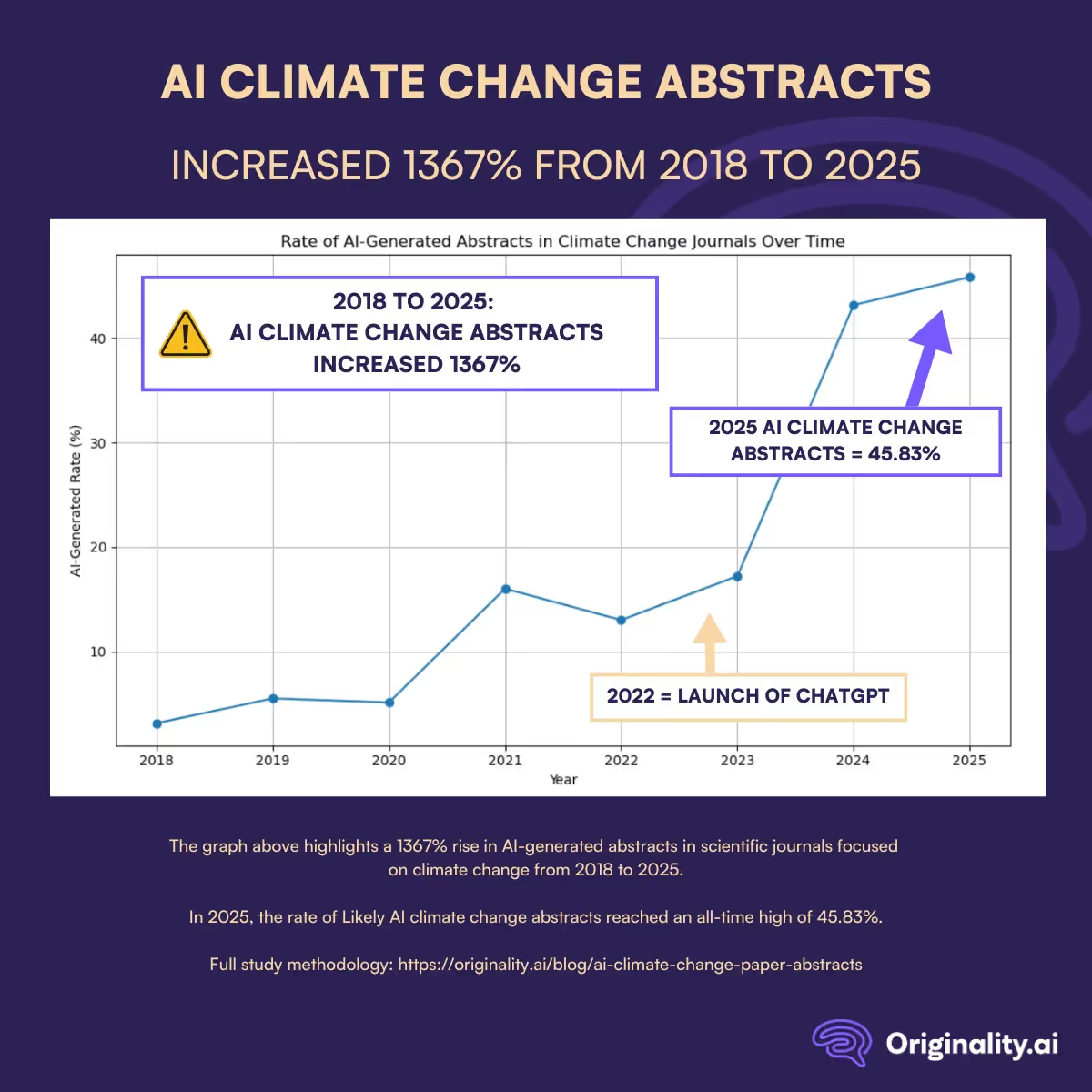

We found that the proportion of AI climate change abstracts in scientific journals rose dramatically from 2018 to 2025.

Check out our quick overview chart to see the rates of Likely AI climate change abstracts by year.

Then, keep reading for a year-by-year discussion of the data.

The rate of AI-generated climate abstracts stayed fairly low and steady from 2018 to 2020:

Then, overall, despite a slight drop in 2022, the trend began to accelerate:

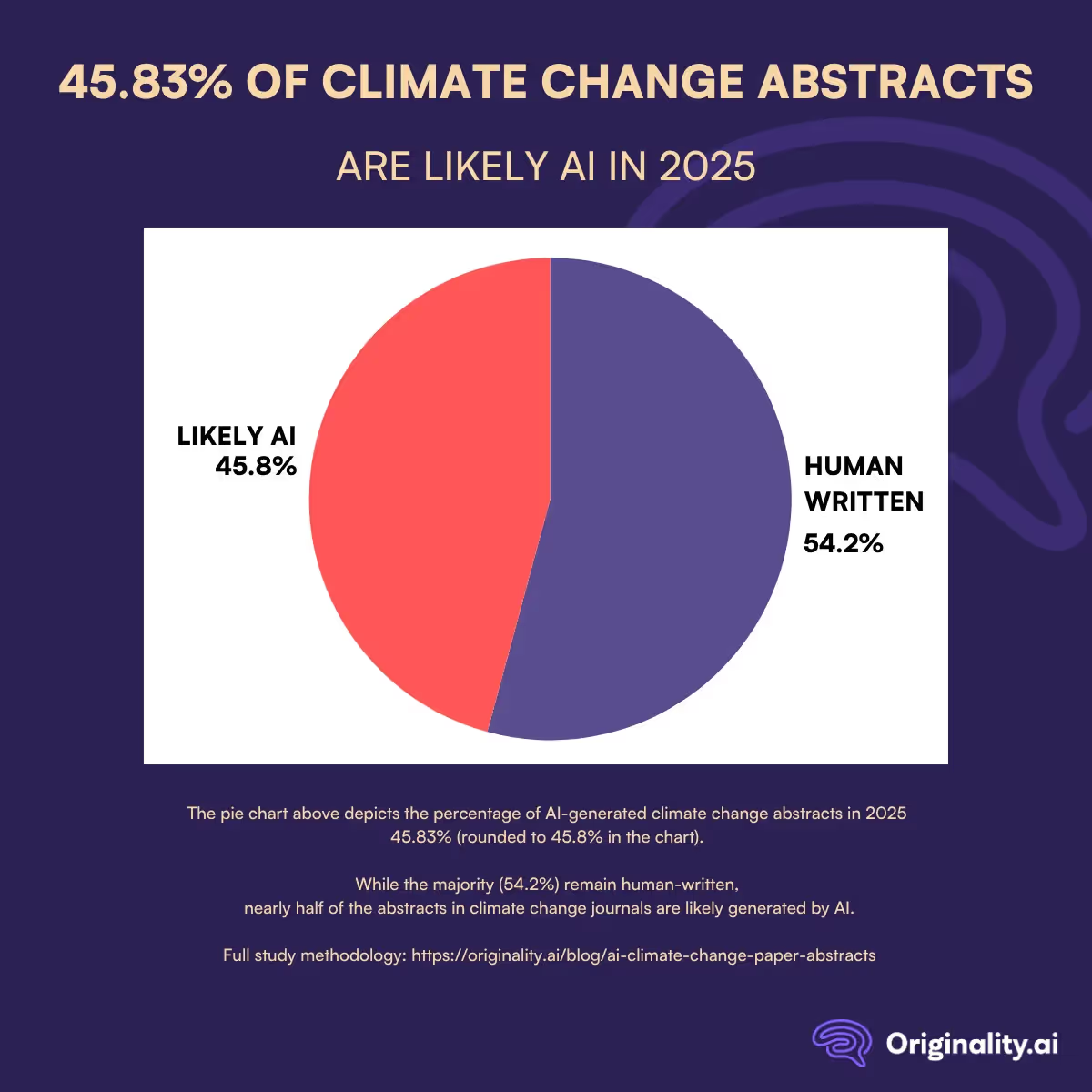

This means that by 2025, nearly half of all climate change abstracts now contain content that is likely generated with the assistance of AI.

Overall, the increase from 2018 to 2025 amounts to a 1367% rise in the rate of AI-generated abstracts.

This exponential growth underscores the rapid adoption of AI tools in academic writing, particularly following the release of ChatGPT at the end of 2022.

Although the sharp rise in AI-generated abstracts from 2018 to 2025 reflects a fundamental shift in how scientific knowledge is being produced and communicated, this trend isn’t limited to academia.

The use of generative AI tools has increased across many industries during this period, especially in online reviews. Previous studies we have conducted found growing rates of likely AI-generated bank reviews, Glassdoor reviews, and lawyer’s office reviews.

So, the finding that 45.83% of climate change journal abstracts in 2025 are likely AI-generated highlights a broader pattern.

It also raises important questions about authorship, accountability, and academic publishing standards.

The prevalence of AI climate change abstracts has several significant implications:

Ultimately, researchers, journals, and institutions will likely need to reconsider policies around AI disclosure, authorship standards, and peer-review processes to preserve the credibility of climate change research and other scientific disciplines.

This study reveals an exponential rise in AI-generated climate change abstracts from 2018 to 2025. Considering the potential implications of this trend, such a significant increase underscores the need for academics, researchers, and publishers to manage the ethical and practical implications of AI in academic writing.

To uphold transparency, trust, and integrity in scientific communication, those in the academic community should consider:

Until more robust guidelines are developed regarding generative AI use in climate change and other scientific disciplines, readers may also consider evaluating abstracts more critically themselves.

Do you think you’re reading an AI-generated abstract? Try Originality.ai’s AI Checker to find out today.

Curious about the trend of AI-generated content on other platforms? Read more:

To study the prevalence of AI-generated abstracts in climate change research, we analyzed scientific abstracts published from 2018 to 2025. Abstracts were collected using the OpenAlex API, filtered by the keyword “climate change,” publication year, and presence of non-empty abstracts, with up to 500 entries per year. A custom function reconstructed the abstracts from OpenAlex's inverted index, preserving key metadata.

Each abstract (minimum 50 words) was evaluated using the Originality.ai API, which provided an AI-likelihood score and binary classification. Scans were repeated if API errors occurred.

All data — including titles, abstracts, metadata, and AI detection results — were compiled into a CSV file using pandas. This dataset supported further analysis, including trends in AI-generated content over time.

MoltBook may be making waves in the media… but these viral agent posts are highly concerning. Originality.ai’s study with our proprietary fact-checking software found that Moltbook produces 3 X more harmful factual errors than Reddit.