It seems like we’re always talking about what AI can do for us. You know, help us boost productivity, answer questions, or brainstorm ideas when we’re stuck. However, how often do we stop and ask what it’s doing to us?

OpenAI and the MIT Media Lab set out to explore that question through a large-scale research collaboration, “Investigating Affective Use and Emotional Well-being on ChatGPT”.

The study focused on how interactions with ChatGPT affected users’ emotional well-being — what they found could change how we think about using and developing AI going forward.

This article breaks down the key insights of the study, including: how the researchers conducted the study, what they found, and why it matters.

To help them understand how people use ChatGPT and how it affects them, OpenAI and the MIT Media Lab carried out two parallel studies.

For their part of the study, the OpenAI team analyzed close to 40 million ChatGPT conversations to get an idea of how people emotionally engaged with their AI (to get insight into affective use patterns).

They had a particular interest in what they called power users, or those who ranked in the top 1000 voice users on any given day.

With user privacy in mind, OpenAI developed a set of automated classifiers called EmoClassifiers V1 to scan conversations for emotional and behavioral cues, like:

At the same time, they also surveyed over 4000 users to compare how people described their emotional experiences with what showed up in the conversation data. They were especially interested in the differences between power users and more typical ones.

Then, MIT Media Lab tested how different types of ChatGPT interactions might affect emotional health over time (to obtain “causal insights” into the impact of different features like model personality and usage type on users).

They ran a 28-day randomized controlled trial with 981 participants randomly assigned to one of nine experimental conditions that included some combination of:

As with the ChatGPT study, the MIT team also had a particular interest in whether changing up the voice affected participants’ emotions. For example, they designed the “engaging” voice to sound more expressive and human to see if it would elicit stronger reactions from participants.

The researchers assigned each participant in the personal or non-personal groups one prompt to use per day, while the open-ended group could use ChatGPT however they wanted.

Regardless of group, though, they expected all participants to use ChatGPT for at least five minutes daily.

To track the participants’ emotional and behavioral changes throughout the study, the researchers monitored psychosocial outcomes using the following scales:

Participants also completed daily check-ins and post-study surveys to reflect on their experiences.

Just like the OpenAI study, the MIT team also used classifiers for the analysis.

This combination of research methods yielded mixed results:

Let’s take a closer look.

Across both studies, most participants used ChatGPT in neutral, task-based ways, not for emotional conversations.

“Emotional engagement with ChatGPT is rare in real-world usage.” - OpenAI

However, the researchers did find that a small group, most notably among power or heavy users, showed signs of higher emotional attachment.

These participants showed attachment by:

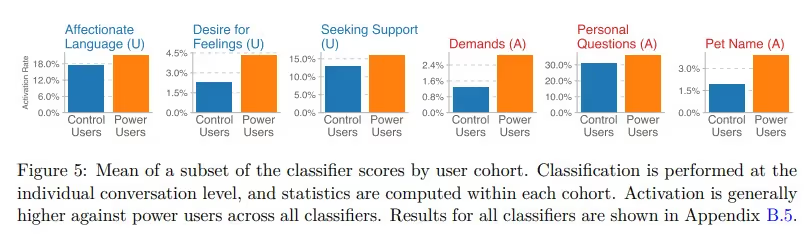

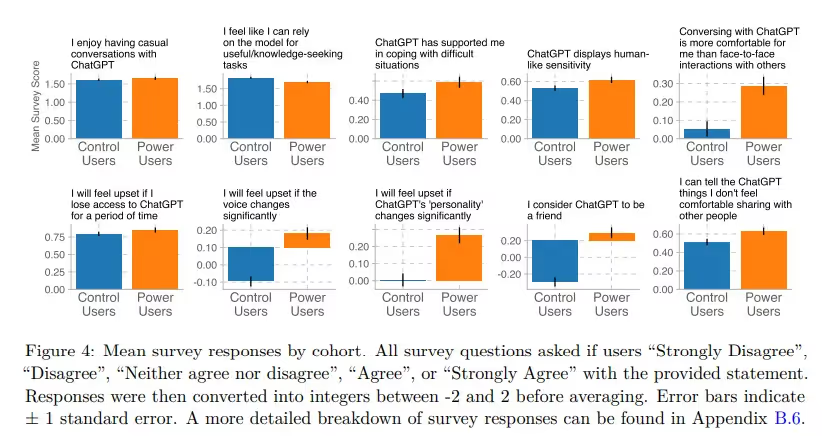

Where there were signs of emotional engagement, power users tended to show higher rates.

When looking at usage, OpenAI found that power users of Advanced Voice Mode:

Essentially, the classifiers found that these power user conversations showed higher rates of validation-seeking and emotional openness with ChatGPT.

Yet, overall, the study notes that both the proportion of users likely to view ChatGPT as a friend was low among both groups (‘control’ and ‘power’), stating “these views remain a minority in both groups.”

So, even though most used ChatGPT as just another tool, some (even if a small group) did start to form more of a personal connection.

In the MIT Media Lab trial, researchers found that participants who used voice, often the “engaging” one, were typically more likely to receive emotional responses from ChatGPT compared to the neutral voice.

“Using a more engaging voice model, as opposed to a neutral voice model significantly increased the affective cues from the model, but the impact on user affective cues was less clear.” - OpenAI and MIT Study

In MIT’s blog summarizing the research, they further highlight that, “Importantly, using a more engaging voice did not lead to more negative outcomes for users over the course of the study compared to neutral voice or text conditions.”

So, the key takeaway is that although the findings indicated that ChatGPT was more likely to respond with an affective cue when participants were using the ‘engaging’ voice-based chat, overall, it did not negatively impact users.

Personal factors did have an impact. Participants who did show signs of emotional engagement with ChatGPT tended to have a few things in common:

“...users who spent more time using the model and users who self-reported greater loneliness and less socialization were more likely to use engage in affective use of the model.” - OpenAI and MIT Study

Another aspect to note is the increasing signs of attachment that the classifiers flagged (as documented by the first part of the study via ‘control’ and ‘power’ users).

For instance, users turning to ChatGPT for comfort, worrying about losing access, or relying on it for emotional support.

This was reflected in some of the survey responses, depicted in the chart above, with users essentially describing ChatGPT as comforting or supportive.

Ultimately, OpenAI and MIT Media Lab’s study revealed that most people do indeed use ChatGPT as a tool. However, it also found that for a small group, these AI conversations can become more personal.

As interactions with AI writing tools and chatbots like ChatGPT get more human-like, humans may start to feel that AI chatbots are more emotionally aware, even when we’re perfectly aware that they’re machines.

This can lead to all kinds of responses from users, with some feeling more supported, some more dependent, and even others who are uncomfortable with the whole situation in the first place (often referred to as AI anxiety).

The results of this study indicate that the way we use AI tools can shape how we handle emotions, ask for help, and relate to other people altogether.

That’s what makes this study worth paying attention to.

Not just because it shows us how people are using AI today, but because it hints at where that use might take us next.

Maintain transparency in the age of AI with the Originality.ai AI Checker and identify whether the text you’re reading is human-written or AI-generated.

Further Reading: